Baur

The Baur Foundation

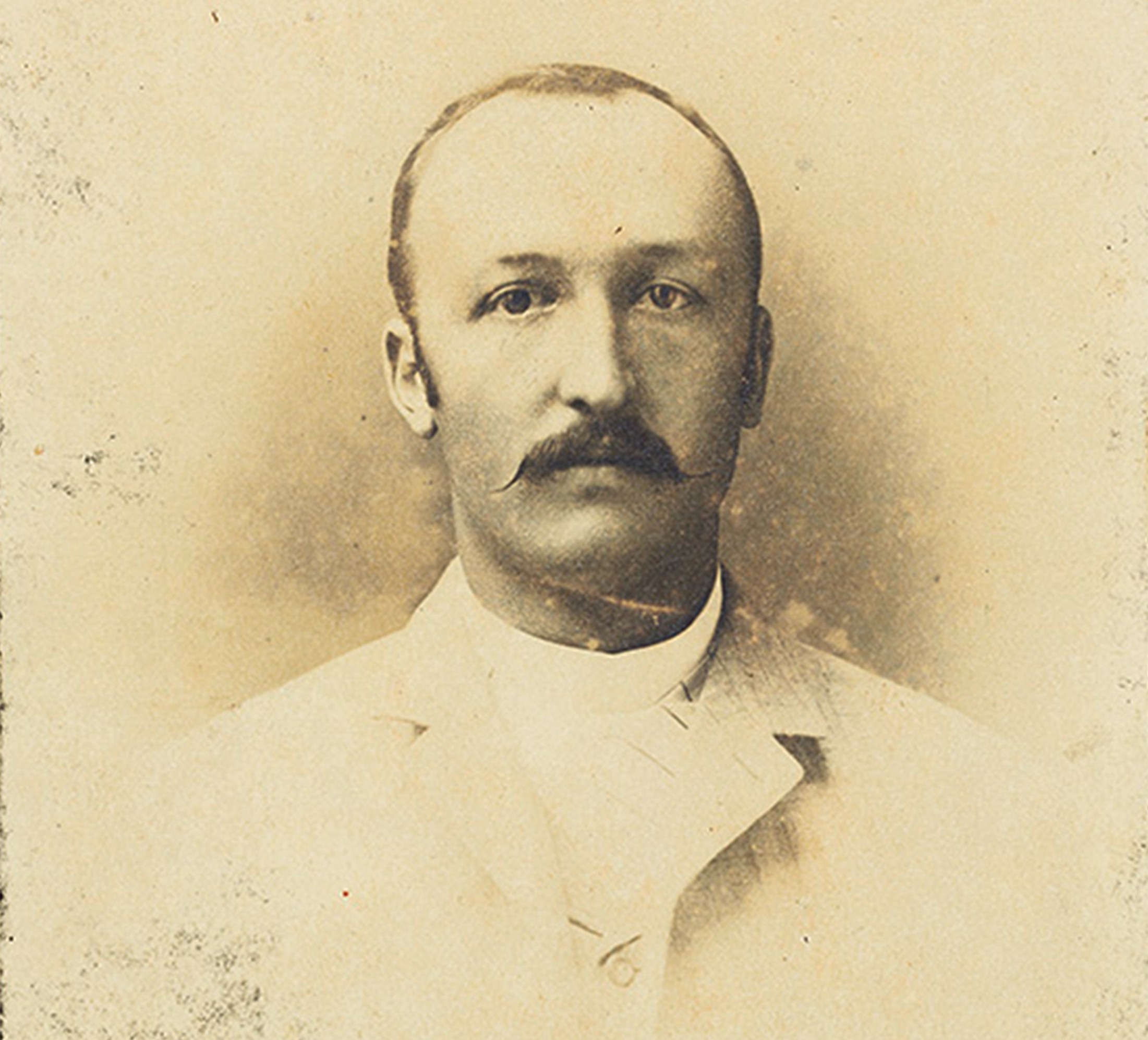

Alfred Baur

Alfred Baur was born in 1865 in the village of Andelfingen (Zurich). Having completed his studies at a Winterthur commercial school, he joined a local trading company which sent him to their branch in Colombo (Sri Lanka). In 1897, Mr Baur founded his own business there, setting up a company to manufacture organic fertilisers; A. Baur & Co. celebrated its centenary in 1997.

In 1906, Mr Baur returned to live in Switzerland, choosing to settle in Geneva, the home town of his wife, Eugénie Baur-Duret’s. He nevertheless continued to manage his business in Colombo, expanding and diversifying it over the years, most notably through the acquisition of several tea plantations.

Mr Baur’s return to Switzerland also marks the beginning of his activities as an art collector, with his first purchases of Japanese ceramics, lacquer ware, netsuke and sword fittings as well as Chinese jades. In all fields of art, he sought out works which displayed faultless craftsmanship and were aesthetically perfect. Alfred Baur’s meeting in 1924 with Tomita Kumasaku, an art dealer based in Kyoto, provided new impetus for his collection. Mr Baur regarded Tomita as an extremely knowledgeable expert, a man of sure and refined taste who understood his own demands and requirements. The major part of Baur’s collections, including many of the most exceptional pieces, was acquired through the guidance of this advisor.

The year 1928 marks an important stage in the development of the collection: this was the moment when Mr Baur began to show an interest in Chinese ceramics, a field which was to become one of his dominant interests. The 756 pieces which he acquired form a coherent collection ranging from the Tang (618-907) to the Qing (1644-1911) dynasties.

Shortly before his death in 1951, Mr Baur purchased a town house in the centre of Geneva with the intention of turning it into a museum for his collections; the museum first opened to the public in 1964.

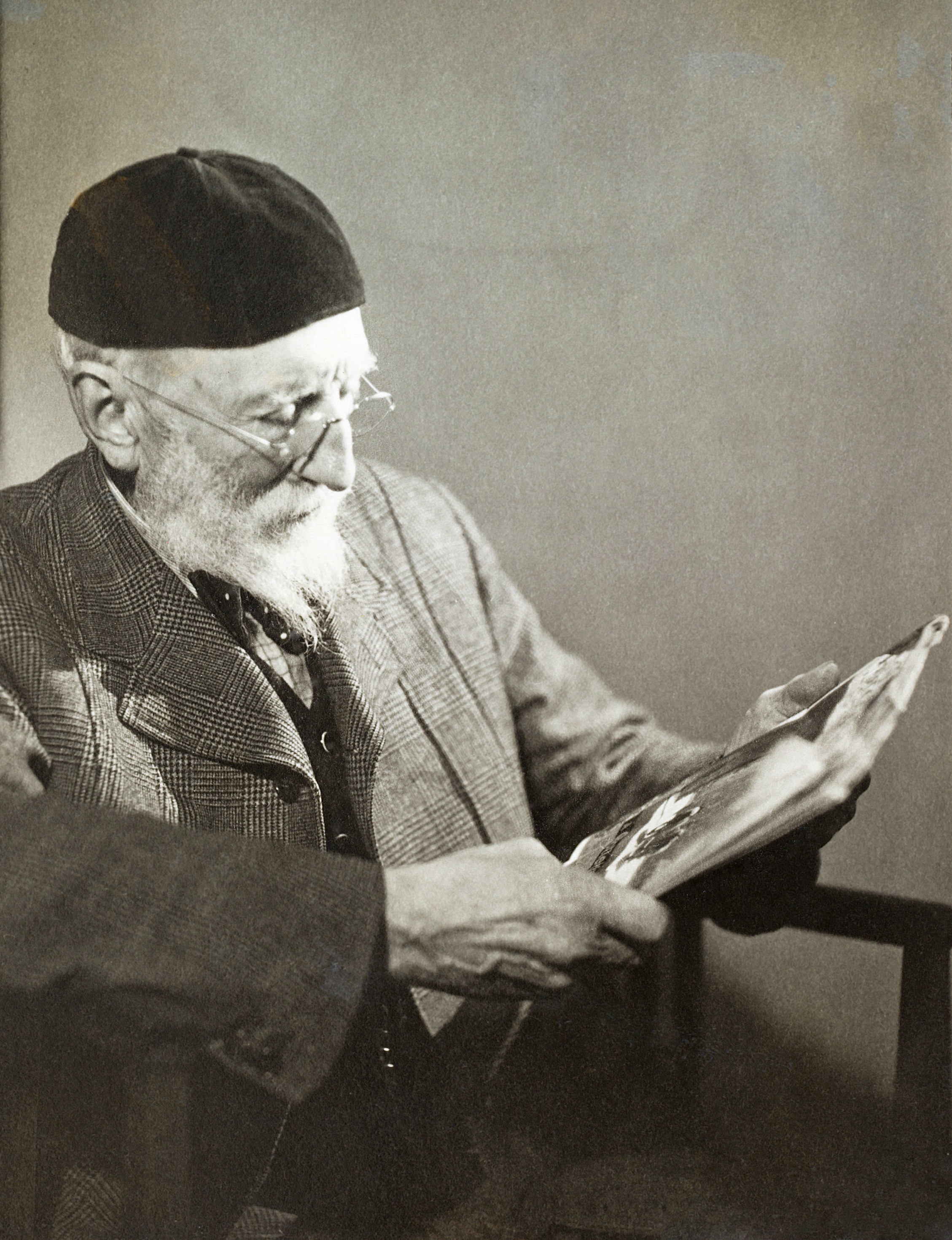

Thomas Bates Blow (1853-1941)

Thomas Bates Blow (1853–1941) was a dedicated merchant and collector who settled in the district of Shimo-Kyoku in Kyoto. A beekeeper, botanist, member of the Linnean Society and the Royal Photographic Society in London, this Englishman, married to a Japanese woman, was an eccentric character very much in the line of British adventurers and explorers. He made a name and fortune for himself with a business he set up producing beekeeping equipment in Welwyn, his hometown. An enthusiastic globetrotter, there was not a continent he did not visit. Thomas Blow was well known in England at the auction houses and by the most important collectors of Japanese art of the period – Joly, Behrens, Tomkinson, Edmunds and Ransom. On his death he bequeathed a collection of Japanese prints to the British Museum.

Alfred Baur, whom he had met in Ceylon through common acquaintances, began to collect Japanese “curios” in 1907 through his intermediary after he had moved to Geneva. Blow supplied him with blades, sabre fittings, netsukes, inro, prints, Satsuma ware, cloisonné, carved ivory statuettes, works in bronze and cabinets decorated with lacquer, but also Chinese objects such as jades, lacquer ware and snuff bottles. Blow was also a knowledgeable advisor who, as from 1919, acquired books on Japanese and Chinese art and catalogues of sales and private collections for his client. With the exception of the prints, however, little trace remains in the Baur Collections of the works Alfred Baur acquired with the help of the Englishman, as the collector sold off a great proportion of them in 1928 when he became more exacting in his choices.

Gustave Loup (1876–1961)

Gustave Loup (1876–1961) was a Swiss merchant born in China who spoke French, English and Mandarin fluently. His father was one of the watch- and clock-makers who left the Val-de-Travers (Neuchâtel) in the 19th century to settle in Canton, Shanghai and Tianjin where he sold watches. It was sometime during the 1920s that this expatriate opened a business trading in antiquities between China and Switzerland, and then a shop – La Chine Antique – in rue Céard in Geneva. The business thrived for some ten years until the Japanese military presence in China rendered purchases and exports impossible. Gustave Loup ended his life in Geneva, where he lived in a large apartment on the Quai des Bergues, packed with a hotchpotch of European and Chinese antiques, furniture, gold- and silverware, figurines, clocks and much more. He was also known for his famous watch collection, which he purchased in China and brought back to Switzerland.

The details of when and how Gustave Loup and Alfred Baur met are unknown, but their correspondence began in 1923. A year later, Gustave Loup received the collector and his wife in Peking. He served as their guide during the only long Asian journey they undertook. A certain respect, followed by trust, marked the relationship between the two Swiss men, who exchanged many opinions on China, its culture and on curios. Baur allowed himself to be charmed and bought numerous objects, at times even entire lots. He then thought carefully about what he had received, kept the most beautiful pieces and sold off those he was less enamoured of. With time, the collector's taste became more precise, his requirements became more particular and he sought out specific pieces. Even though Gustave Loup never took the place of the Japanese dealer Tomita Kumasaku (1872–1953) in the forming of the collections, Alfred Baur always retained a special affection for the Swiss trader.

Tomita Kumasaku

The son of a sake brewer from Hyôgo prefecture, Tomita Kumasaku (1872-1953) was sent to England in 1897 by the Japanese trading firm for which he was working. In 1903, he joined the London branch of Yamanaka & Co., a well-established art dealer based in Osaka. Tomita later became manager of the branch and remained in London until 1922, when he returned to his native land and settled in Kyoto.

During his years at Yamanaka’s, Tomita played an important role in the creation of the large Oriental ceramic collections which were being formed in London at the beginning of the 20th century. General interest in this domain had been furthered at the time by a major Japanese art exhibition organised in 1915 by the British Red Cross, for which Tomita was a commissioner and co-author of the catalogue, as well as by the establishment in 1921 of the Oriental Ceramic Society in London.

Tomita Kumasaku first met Alfred Baur and his wife during their trip to Japan in 1924. He had been recommended to the Swiss collector by Thomas Blow, an English art dealer who was acting then as his art advisor. After their first meeting, a solid trust and friendship were established between the two men, and together, over the next thirty years, they would shape the collections that we know and enjoy today.

The building

Built at the very beginning of the 20th century, the private residence of the rue Munier-Romilly was acquired by Alfred Baur shortly before his death in 1951 with a view to exhibiting his Asian art collection to the public. In a letter, he wrote that he had found there an intimate setting which would allow a museum to be created in which visitors “will not have the impression of a museum, but that of a private house, where all the artworks can be examined at leisure”.

Plans for a conversion of the building were drawn up in the early 1950s by the architect’s office Tréand père & fils. But the work itself was only initiated in 1963, and Christoph Bernoulli was commissioned to do the interior decoration. The rooms and display cases were personalised, in keeping with the works to be exhibited in them. The ground floor and first floor were fitted out with luxurious refinement: Chinese carpets, English, French or Chinese furniture, Louis XVI wood panelling, and mahogany or oxidised-metal display cases, were to provide the intimate atmosphere and personal touch by which the Baurs set so much in store. The ground floor houses the ceramics of the Tang (618-906), Song (960-1279), and Ming (1368-1644) dynasties, as well as the jades, while the first floor is devoted to Qing dynasty (1644-1911) imperial ceramics. The second floor, which is reached by a staircase with a red-lacquered wooden banister, is set aside for Japanese art. In these rooms, the Kakiemon, Imari and Nebashima porcelains are exhibited together with the sword fittings, netsuke, prints and lacquer writing boxes, inrô, and other objets d’art.

The Baur Collection opened to the public on the 9th of October 1964. In 1995, major extension work was undertaken in the basement floors to allow the creation of temporary exhibition rooms as well as a seminar room equipped for university teaching of art history. The work was carried out by the office Baillif & Loponte under the direction of the architect Joël Jousson. The extension was inaugurated on the 4th of December 1997.

In 2008, due to the lack of insulation of the outer walls and the run-down state of the furnishings of the second-floor rooms dedicated to Japanese art, a complete renovation of this floor was undertaken under the direction of the Genevese firm of architects, Bassi & Carella. The new galleries, which opened to the public in September 2010, provide a considerably larger surface area than before, thus permitting the presentation of categories such as Satsuma ware and cloisonné which had not been shown previously. A rotating selection of Alfred Baur's important collection of Japanese prints is now exhibited in a specially designed display cabinet. Finally, the Japanese galleries are completed by a tatami-covered space inspired by the traditional tea house in which the objects used in the tea ceremony - calligraphy, flower vase, bowls, etc. - can be appreciated in situ. Throughout these rooms, care has been taken to maintain the elegance and excellence which have been the hallmark of all previous work and have resulted in the unique atmosphere of this museum.

The Japanese garden

The Japanese garden, born of the desire to create a living space for an 18th-century lantern, occupies an area of some fifteen meters by five, and is an invitation to journey or to dream.

Located above the museum basement, it could only fall into the category known as kare sansui, or dry gardens, in which raked gravel symbolises real water. Composed of 20 stones, all of which come from the Upper Valais region of Switzerland, the garden is designed to be seen from several fixed viewpoints, either from the ground floor French windows, or from the exhibition rooms of the first floor, from which it turns into an aerial view of the Japanese islands.

In such gardens, strongly influenced by Zen Buddhism, the stone compositions are rich in symbolism, some of which has been expressed here.

Three standing stones form a triad known as the Three Venerable Ones; present in 70% of gardens, this group protects the residence from evil spirits.

A group of nine stones, strongly structured, suggests a wild coastline, a shore of cliffs beaten by violent waves.

Five stones form the Crane peninsula, with two stones placed diagonally to stand for the open wings of the bird, and the other three representing the neck, body and tail.

To the left, lies a Turtle island, its stones depicting the shell, head and flippers; to the right of the pine, a small stone represents a young turtle.

Finally, a solitary reef stone symbolises the Japanese archipelago emerging from the depths of the Pacific Ocean.